| See some samples of the spectacular photographs and examples of the quality of text from the book.

(PLEASE NOTE THAT THE IMAGES ON THIS WEBSITE ARE COVERED BY COPYRIGHT ©. NO CONTENT MAY BE REPRODUCED WITHOUT PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM THE AUTHOR)

I HOPE YOU GET AS MUCH ENJOYMENT FROM READING THIS BOOK AS I DID IN WRITING IT. GOOD FISHING AND VIEWING, ALL! Ern Grant

|

|

Snapper

Pagrus auratus (Bloch & Schneider)

Photo: Ern Grant

Also known as a Squire, the Snapper is the target of every Australian saltwater fisherman – and having caught one, to catch one even larger. The older fish develop a great keeled bump over the nape; the swelling over the snout becomes very prominent. Reaching 43 lb in our cooler waters, Queensland-caught fish rarely exceed 24 lb. Baits must be as fresh as possible: live Yellowtail; large Hardyheads; big Soldier-crabs; and XOS squid-heads. |

|

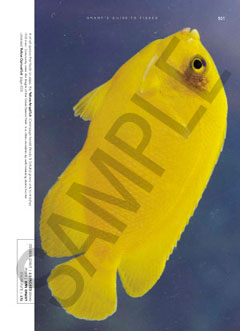

Yellow-faced Angelfish

Pomacanthus xanthometapon (Bleeker)

Photo: Ern Grant

The superbly-coloured Angelfishes of our warmer waters are typically coral-reef forms, all of them known by the strong rearward-facing spine set at the lower edge of the gill-cover. This magnificent Yellow-faced Angelfish is one of the largest and most striking of the group, reaching 15.5 inches. It is often seen by divers on the northern sector of the Great Barrier Reef, such as The Cod-Hole at Cormorant Pass. |

|

Coral Trout

Plectropomus maculatus (Bloch)

Photo: Ern Grant

The scientific classification of our Coral Trouts remains unresolved. I prefer to recognise only three species, attaching colour-phase names to some, thus:

- The common and “typical” Coral Trout, Plectropomus maculatus (Bloch), with three colour-phases:

- the usually-seen Small-spotted, or leopardus colour-phase;

- the less common Bar-cheeked, or maculatus colour-phase;

- the scarce Footballer Trout: the laevis colour-phase;

- the rare Passionfruit Trout Plectropomus areolatus (Ruppell)

- the equally-rare Lined Coral Trout Plectropomus oligacanthus Bleeker.

No Barrier Reef fisherman ever becomes blasé over the capture of a decent-sized Coral Trout – say, a fish of 12 lb or better. The cognoscenti know to fish the edges and ledges of the coral outcrops at anchor – never on the drift, baiting with whole-fish such as Fusiliers, Hardyheads and Murray Island Sardines. Jigging the bait always produces the sharp double-tap as the Trout seizes the bait to crush and kill it. Then, the briefest wait before the fish makes its high-speed dash for cover – stopped only by a very hard strike to set the hook and lift the Trout’s head up. If the fish is gentled for only a second, it planes down to take refuge among the coral outcrops. I have taken Coral Trout on the Reef to a weight of 44.3 lb; but such fish are rare. |

|

Red Emperor

Lutjanus sebae (Cuvier)

Photo: Morgan Grant

One of the real prizes for the deep-water Barrier Reef angler, the Red Emperor grows to a massive 48 lb. It fights without let-up every foot of the way up to the boat. The most striking aspect of its glowing bright-pink coloration is seen in the scarlet broad-arrow over the flanks and face, so typical of the old-time convict dress. Most vividly seen in younger fish, these are (rightly) called: Government Bream. The Red Emperor’s edible qualities are first-rate. Though usually taken on large cut-fish baits, I far prefer to use octopus tentacles that have been sliced into thin ribbons and festooned on to the hook. |

|

Big-Spot Triggerfish

Balistoides conspicillum (Bloch & Schneider)

Photo: Ern Grant Once seen, never forgotten. This is a strikingly beautiful fish that is prized for aquarium display. The temptation should be resisted to dabble the fingers in the water to coax the fish to come close; I have twice seen it come gracefully to the offered finger-tips, only to lunge forward at the last moment, taking out a piece of skin and tissue, - to the dabblers’ consternation. I have in mind an unforgettable occasion when a large concrete pool at Heron Island held an assembly of Reef critters – including an 8-inch Big-spot. It had grown sinfully wise in the ways of aquaria, including the meaning of fingers waggled in the water – when it would approach the waggler, swimming canted over to one side – for all the world like a child learning to ride a bicycle. Came the day when a rubber-clad diver climbed into the pool, pretending to photograph some of the denizens in the hip-deep water – while crowds of ecstatic tourists photographed him at his onerous scientific duties. The Triggerfish obviously felt left out of this carnival; swam quietly over to inspect the diver’s bare toes; and as I watched in wild surmise, moved delicately in to scoop out a mouthful of toe. I have never, never killed a Big-spot since. |

|

Blue Tang (Wedge-tailed Tang)

Paracanthurus hepatus (Linnaeus)

Photo: Ern Grant

The Tangs and Surgeonfishes are a warmwater group, many of them coral-reef forms. Feeding on marine vegetation, they are rarely captured by anglers – but are vulnerable to spearfishermen, who learn soon enough that the fish are so strongly-tainted as to be just about inedible. The Family is characterised in having a needle-sharp spine set on either side of the tail base; usually carried flat against the body, it can be held erect for defence, lacerating the fingers of unwary handlers. The Wedgetailed Blue Tang is one of the most colourful of the group; the upper and lower margins of the tail enclose a broad bright-golden wedge – the feature for which it is named. Prized for aquarium display, this lovely little fish attains 10.5 inches. |

|

Yellow-mouth Moray Eel

Gymnothorax nudivomer (Playfair & Gunther)

Photo: Ern Grant

The Morays, or Reef-eels, are a group of large marine Eels seen throughout Australian waters, including the Great Barrier Reef. They are effective scavengers, tackling quite large prey in a manner that shows the origin of their name: the Knot-Eels. The target is seized and held fast with the great backwardly-directed fangs. A simple overhand knot forms at the tail; it slides up along the flexible body until it is locked against the prey. The Moray then hauls its head back through the knot, exerting immense pressure until a large mouthful of flesh is ripped away. Most of the Reef-eels are aggressive; they can and do attack without apparent provocation. Any diver who attempts to frolic with a Moray is risking an immediate and spectacular injury. In fact, in 1996 a diver had her right arm so mauled by a big Barrier Reef Moray that it was necessary to amputate the limb. The aggressive and spectacularly-marked Yellow-mouth Moray attains 4.5 feet, and is known by the bright yellow lining to the mouth and the large white spots over the body. Its teeth are saw-edged. |

|

Beaked Leatherjacket

Oxymonacanthus longirostris (Bloch & Schneider)

Photo: Ern Grant Known by the furry or prickly nature of the skin, the Family of Leatherjackets carry a strong (but non-poisonous) dorsal spine that can be locked upright. The locking arrangement is so secure that trying to force the spine back will break it rather than depress it. While some species can exceed 30 inches in length, the little Beaked Leatherjacket is a coral-reef form attaining only 3.5 inches. It is commonly seen in the tidal pools of the Great Barrier Reef, usually sheltering close to outcrops of living Staghorn corals. Its normal swimming action is a slow drift, accomplished by a gentle rippling of the soft dorsal and anal fins – until it is threatened by people like myself, armed with a small-mesh dip-net, when it disappears in a blur of motion. The white spots over this fish’s pelvic flap show it to be a male. |

|

Striped Sea-perch (or Hussar)

Lutjanus vitta (Quoy & Gaimard)

Photo: Ern Grant

Growing to 15 inches, the Striped Sea-Perch is commonly taken by linefishermen the length of the Great Barrier Reef, thence westwards into tropical Western Australia. It is known by the broad chocolate-brown ribbon that runs from the snout to the tail. Also called a Hussar, it differs from the more colourful “true” Hussar (Lutjanus adetii (Castelnau)) in that the body-stripe of this related glowing-pink form is bright golden, also running snout-to-tail. Both of these are worthwhile panfishes; but their size usually condemns them to be tossed into the bait-bucket, to be used for cut-fish baits. |

|

Coral Cod

Cephalopholis miniatus (Forskal)

Photo: Ern Grant

This beautiful little fish is commonly seen by linefishermen working along the Great Barrier Reef, ranging out to Westralian warmwaters. Growing to 18 inches, it will rise with surprising energy and speed to attack a lure trolled high above the stands of corals among which it shelters. Rightly prized as a tablefish, it is sometimes confused with the Coral Trout itself; but is readily distinguished in that the tail is rounded, where the Coral Trout’s tail is square-cut, or curved slightly inwards. This gives it its name of Round-tailed Trout. |

|

Tomato Clownfish (or Anemonefish)

Premnas biaculeatus (Bloch)

Photo: Ern Grant

The Anemonefishes, or Clownfishes, are a colourful group, almost unique in their close association with large tropical Anemones. The fish live among the stinging tentacles of these Anemones, some species of which form into quite large colonies over the shallow coral lagoons. The benefits to the fish itself far outweigh those to the Anemone; the fish are protected from attack by other fish by the Anemone’s stinging tentacles, “bathing” among them by day and settling down deep among them by night. Frequently, Anemonefish that find some food too large to be eaten will carry it to the Anemone and deposit it deep among the tentacles. The unmistakable little Tomato Clownfish grows only to 5 inches; more commonly seen on the Reef’s northern sector, youngsters carry two narrow white vertical ribbons over the tomato-red body. A third develops in older fish.

|

|

![]()